Bridging Technology and Conservation: Reflections from HCV Network’s Project Manager Mirzha Hanifah on her work in three landscape initiatives in Indonesia

In mid-July, I made my first trip to Seruyan Regency as part of the Jurisdictional Approach (JA) work conducted with HCVN’s member and partner, Kaleka. The purpose of the visit was to support a public consultation to validate the indicative High Conservation Value (HCV) map. This consultation was combined with participatory mapping work that Kaleka had facilitated in each village. Within the JA process, both participatory village mapping and public consultations play a crucial role, ensuring that the spatial information used in decision-making is not only technically accurate but also socially recognised.

Accustomed to interpreting landscape-scale patterns and changes through satellite imagery and spatial data, the long journey to Seruyan Hulu gave me the chance to reflect on how social verification, such as public consultations, becomes an important bridge that helps indicative HCV maps move beyond technical accuracy and become relevant for the people who manage and depend on the landscape.

Starting in Seruyan, Central Kalimantan

Seruyan stretches from the Java Sea in the south to the border with West Kalimantan in the north, with the Seruyan River connecting upstream and downstream areas. Its landscape ranges from lowlands, peatlands and swamps to dense forests in the north. Within the extensive oil palm estates that drive the local economy, the area still holds rich conservation values that require collective attention. To the south, Seruyan borders Tanjung Puting National Park, which reminded me of Camp Leakey and the long term work of Birutė Galdikas in studying great apes as a way to understand human evolution.

My work is different from the long term field studies carried out deep in the forest. Most of my time has been spent on spatial analysis and interpreting landscape change, yet my experience in Seruyan reminded me that what appears on the screen covers only part of the story. The rest exists on the ground within the relationships between ecosystems, communities, and the values that connect them. These elements ultimately determine whether our analyses are meaningful for those who manage and protect HCV areas.

From this process, I learned that one of the most important skills in the HCV Approach is the ability to listen. In a landscape context, listening means creating space for dialogue with stakeholders such as local government institutions, village communities, customary groups, private sector actors, and local organisations. This process is intended to be more than a formality. It aims to align perspectives so that indicative HCV maps can develop from technical interpretations into representations of reality that are recognised and shared by the people living in the landscape.

My work in Seruyan also reinforced the idea that technology provides only part of the answer. Remote sensing can show where changes occur, but the actions that follow depend on the people who live and work in the landscape. Indicative HCV maps gain their strength when they are validated through public consultation, aligned with village level participatory maps, discussed in multi stakeholder forums, and understood by their end users. The Jurisdictional Approach makes this process more efficient because all actors are encouraged to work within one shared framework.

From Seruyan, I learned that successful monitoring is not only about accurate data. It depends on how well stakeholders are connected and how ready they are to work together when they need to respond to change. The strength of the collaboration ecosystem often determines the strength of the monitoring itself.

Moving on to Merauke in South Papua

My learning did not end in Seruyan. The following month, I was once again brought into a landscape with its own complexity. This time I travelled to Merauke in South Papua Province to begin the implementation of the Forest Integrity Assessment (FIA) in the Danau Bian conservation area. If Seruyan taught me the importance of listening, then Merauke taught me that monitoring has dimensions that go far beyond detecting change.

Papua has always held a special place in my memory. It is often described as one of the last forest frontiers, not only because of the remaining forest extent but also because of its ecological significance. During the early morning flight from Jakarta, the continuous expanse of forest visible through the window at sunrise was a reminder of the scale and importance of the region.

In Merauke, I learned to integrate the FIA as a complement to other monitoring tools I had used in the past. The FIA is designed not only to identify whether forest cover remains but also whether the ecological integrity of the forest is still sufficient to support biodiversity, soil and water protection, and resilience to natural pressures.

My previous experience helped me interpret spatial patterns such as fragmentation and weekly or monthly alerts of land cover change. Working with the FIA added a deeper layer of understanding. Monitoring is not only about what is lost but also about the quality of what remains. Through this assessment, forest conditions are examined more thoroughly including structure and composition, disturbance levels, connectivity across habitats, regeneration patterns, and the presence of key species.

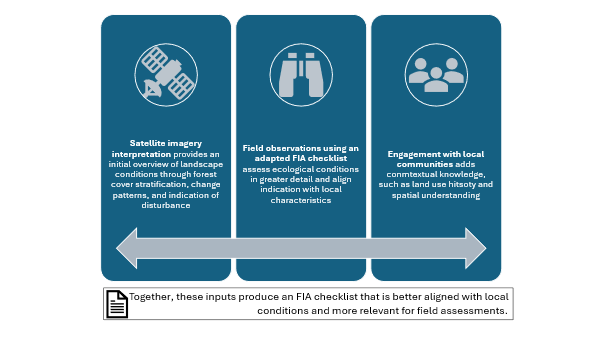

Throughout the process, I worked with field teams, conservation area managers, and local communities. The adaptation of the FIA relied on three sources of information: remote sensing data, field observations, and local knowledge. The combination of these elements allowed us to adjust the checklist so that it reflected the ecological and social context of the Danau Bian landscape.

Implementing the FIA in Merauke also helped clarify how different monitoring tools complete one another. Near real time alerts are valuable for detecting change within weeks or months, for example when new openings appear. These alerts, however, do not explain the ecological condition after the change has occurred. The FIA fills this gap through periodic and in depth evaluation. Its annual results can indicate whether conservation management is effective or requires improvement.

From this experience, I learned that near real time alerts provide warnings, while the FIA provides context and direction. Used together, they support a monitoring system that is more complete: fast enough to identify change and detailed enough to determine whether forest values are being maintained.

And last but not least, the infamous Aceh in Sumatera

My experiences in Seruyan and Merauke reminded me of the basic principles often mentioned by long-term wildlife researchers such as Birutė Galdikas and Dian Fossey. Galdikas once reflected on the difficulty of working in remote areas that are often overlooked and not well documented. Many of the most significant conservation challenges exist in places like these. Remote sensing becomes especially important in such contexts because it allows us to observe change in areas that are very difficult to reach. Yet, as Galdikas emphasised, technology still relies on local knowledge and collaboration to be meaningful.

Fossey’s principles of conservation, which include continuous monitoring, timely response to threats and targeted intervention, reinforce the idea that monitoring is not only about detection. It involves making decisions based on the information we gather. Advances in remote sensing and cloud computing now allow monitoring to be conducted more rapidly and across wider areas. But technology does not eliminate the need for interpretation and action.

After returning from Merauke, we facilitated a capacity building activity on HCV Screening with stakeholders in Aceh Province. The activity involved local government institutions working in forestry, agriculture, and plantation sectors, along with civil society organisations in the province.

Through this desktop assessment, we mapped the potential presence of HCV and its associated threats as a first step before conducting field work. The discussions made it clear that land cover maps alone were not enough. Stakeholders needed to understand which values must be protected, what threatens these values, and how this information should guide action.

The screening process became a point of alignment. It helped stakeholders establish shared understanding, allocate resources, and prioritise areas for participatory mapping, field verification, and full assessment. From this experience, I learned that data only gains meaning when the values inside it are understood together.

Across Seruyan, Merauke, and Aceh, three insights shaped how I now connect remote sensing with the HCV approach. Data will not move without collaboration. Rapid detection must be complemented by deeper evaluation. Monitoring without understanding values will always remain incomplete.

Reflections - technology is an incredible tool but ultimately people and partnerships are at the heart of driving conservation

Technology helps to overcome the limitations of conventional monitoring methods that depend on human resources, funding, and physical access. Yet these past six months at HCVN have reminded me that technology is only half of the story. The other half lies in ecological, social, and cultural values. After working across three very different corners of Indonesia — Seruyan, Merauke, and Aceh — I have come to understand that forest monitoring can no longer be viewed merely as a technical exercise. It is a journey that brings together data, values, social context, and the ecological realities found on the ground.

I am certain that the coming year will bring the next learning curve, helping me complete more pieces of the larger puzzle of how monitoring and conservation function in practice. This journey has shown me that understanding a landscape is an ongoing process, and each new experience continues to shape the way I see and approach this work.

Related Posts

Menjembatani Teknologi dan Konservasi: Refleksi Project Manager HCV Network, Mirzha Hanifah, dari Tiga Inisiatif Lanskap di Indonesia

Read MoreBridging Technology and Conservation: Reflections from HCV Network’s Project Manager Mirzha Hanifah on her work in three landscape initiatives in Indonesia

Read MoreMusim Mas and HCV Network Pilot Farmer-Friendly High Conservation Value Tool in West Kalimantan

A New Approach to Conservation in Smallholder Landscapes

Read MoreOur Partnerships

Alongside many global initiatives, our work with partners promotes practices that help meet the global Sustainable Development Goalsand build a greener, fairer, better world by 2030.

Femexpalma

In April 2022, FEMEXPALMA and the HCV Network signed a 5-year cooperation agreement to promote sustainable production of palm oil in Mexico. FEMEXPALMA is a Mexican independent entity that represents palm production at the national level and promotes the increase of productivity in a sustainable way.

With global markets becoming stricter, for Mexican producers to be able to export to key markets such as the European Union, they must meet strict requirements such as certification by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO). To be certified by RSPO, the HCV Approach must be applied prior to the establishment of any new oil palm plantations. With this cooperation agreement, the HCV Network will support FEMEXPALMA’s members and allies to design better strategies to identify, manage and monitor High Conservation Values and support smallholders to achieve RSPO certification and implement good agricultural practices.

High Carbon Stock Approach

The High Carbon Stock Approach (HCSA) is an integrated conservation land use planning tool to distinguish forest areas in the humid tropics for conservation, while ensuring local peoples’ rights and livelihoods are respected.

In September 2020, HCV Network and the HCSA Steering Group signed a five-year Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) to strengthen their collaboration to conserve forests and uphold community rights in tropical forests. The HCS and HCV Approaches are cornerstones of corporate no deforestation and conservation commitments, and increasingly for actors working at different scales. The collaboration aims to further support effective implementation of these commitments through increased uptake of the HCV and HCS tools.

Through this MoU, HCSA and HCVRN are pursuing two main strategic goals:

- Strive to promote the application of the two approaches in tropical moist forest landscapes and explore further opportunities for collaboration.

- Ensure that, where the two approaches are applied together, this happens in a coordinated, robust, credible, and efficient manner, so that HCS forests and HCVs are conserved, and local peoples’ rights are respected.

World Benchmarking Alliance

From May 2022, the HCV Network is an ally at the World Benchmarking Alliance (WBA). WBA is building a diverse and inclusive movement of global actors committed to using benchmarks to incentivise, measure, and monitor corporate performance on the SDGs, and will assess and rank the performance of 2,000 of the world’s most influential companies against seven systems of transformation by 2023.

The scope of WBA’s circular transformation was expanded to cover nature and biodiversity as recognition of the need for greater understanding, transparency and accountability of business impact on our environment. The WBA Nature Benchmark was launched in April 2022, which will be used to rank keystone companies on their efforts to protect our environment and its biodiversity. As HCV Areas are recognised as key areas important for biodiversity, companies that publicly disclose their actions to identify and protect HCVs will contribute to the assessment of their performance against the benchmark.

Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures - TNFD

The Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) is a global, market-led initiative, established with the mission to develop and deliver a risk management and disclosure framework for organizations to report and act on evolving nature-related risks, with the aim of supporting a shift in global financial flows away from nature-negative outcomes and toward nature-positive outcomes.

In April 2022, the HCV Network joined the TNFD Forum. The TNFD Forum, composed of over 400 members, is a world-wide and multi-disciplinary consultative network of institutional supporters who share the vision and mission of the task force.

By participating in the Forum, the HCV Network contributes to the work and mission of the taskforce and help co-create the TNFD Framework which aims to provide recommendations and advice on nature-related risks and opportunities relevant to a wide range of market participants, including investors, analysts, corporate executives and boards, regulators, stock exchanges and accounting firms.

Aquaculture Stewardship Council

The Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC) is the world’s leading certification scheme for farmed seafood – known as aquaculture – and the ASC label only appears on food from farms that have been independently assessed and certified as being environmentally and socially responsible. In 2021, the HCV Network and ASC formalised their collaboration through a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU). The MoU represents the first step in a fruitful relationship aimed at conserving HCVs in aquaculture. Although, existing guidance on the use of the HCV Approach currently focuses mainly on forestry and agriculture, the HCV Approach is however generic, and in principle also applicable to aquatic production systems. Through this MoU, this is recognised by the Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC) in their ASC farm standard, in which the protection of HCV areas is mentioned in the context of expansion

Accountability Framework Initiative

The Accountability Framework initiative (AFi) is a collaborative effort to build and scale up ethical supply chains for agricultural and forestry products. Led by a diverse global coalition of environmental and human rights organizations, the AFi works to create a “new normal” where commodity production and trade are fully protective of natural ecosystems and human rights. To pursue this goal, the coalition supports companies and other stakeholders in setting strong supply chain goals, taking effective action, and tracking progress to create clear accountability and incentivize rapid improvement. In July 2022, the HCV Network joined AFi as a Supporting Partner. AFi Supporting Partners extend the reach and positive impact of the AFi by promoting use of the Accountability Framework by companies, industry groups, financial institutions, governments, and other sustainability initiatives, both globally and in commodity-producing countries.

Biodiversity Credit Alliance

The Biodiversity Credit Alliance (BCA) is a global multi-disciplinary advisory group formed in late 2022. Its mission is to bring clarity and guidance on the formulation of a credible and scalable biodiversity credit market under global biodiversity credit principles. Under these principles, the BCA seeks to mobilize financial flows towards biodiversity custodians while recognising local knowledge and contexts.

The HCVN joined the BCA Forum in August 2023 to learn more from the many organizations already coming together to find effective pathways to opening up credit-based approaches, and how to contribute our knowledge and experience of years of working in a practical way, often with global sustainability standards and their certified producers, to protect what matters most to nature and people.

.webp)

.webp)

Nature Positive Forum

The Nature Positive Initiative is a group of stakeholders coming together to find ways to unlock success and achieve Nature Positive - a global societal goal defined as ‘halt and reverse nature loss by 2030 on a 2020 baseline, and achieve full recovery by 2050’, in line with the mission of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework.

Core work includes preserving the integrity of ‘Nature Positive’ as a measurable 2030 global goal for nature for business, government, and other stakeholders, and providing the tools and guidance necessary to allow all to contribute. The initiative also advocates for the full implementation of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework by governments and other stakeholders.

IUCN

IUCN is a membership Union uniquely composed of both government and civil society organisations. It provides public, private, and non-governmental organisations with the knowledge and tools that enable human progress, economic development, and nature conservation to take place together.

Created in 1948, IUCN is now the world’s largest and most diverse environmental network, harnessing the knowledge, resources and reach of more than 1,400 Member organisations and around 15,000 experts. It is a leading provider of conservation data, assessments, and analysis. Its broad membership enables IUCN to fill the role of incubator and trusted repository of best practices, tools, and international standards.

IUCN provides a neutral space in which diverse stakeholders including governments, NGOs, scientists, businesses, local communities, indigenous peoples’ organisations, and others can work together to forge and implement solutions to environmental challenges and achieve sustainable development.

Working with many partners and supporters, IUCN implements a large and diverse portfolio of conservation projects worldwide. Combining the latest science with the traditional knowledge of local communities, these projects work to reverse habitat loss, restore ecosystems, and improve people’s well-being.

Get Involved

Our Mission as a network is to provide practical tools to conserve nature and benefit people, linking local actions with global sustainability targets.

We welcome the participation of organisations that share our vision and mission to protect and enhance High ConservationValues and the vital services they provide for people and nature. By collaborating with the Network, your organisation can contribute to safeguarding HCVs while gaining valuable insights and connections that support your sustainability goals.

We are seeking collaborative partners to help expand and enhance our work, as well as talented professionals who can join the growing Secretariat team, and for professionals who can contribute to the credible identification of High Conservation Values globally.

Join us in securing the world’s HCVs and shaping a sustainable future.